Ethiopia

Ethiopia

Community health workers lead the fight against malaria

“…To eliminate – and ultimately eradicate – malaria would pay a massive return on investment. Scaling up coverage of effective malaria control tools in the 29 highest-burden countries [which includes Ethiopia] would yield an estimated gain in Gross Domestic Product of 283 billion U.S. dollars – which is eight times more than the associated costs of 35 billion dollars. Our fight against malaria is therefore not just the right thing to do, it’s the smart thing to do.”

— Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO Director-General, former Ethiopia Minister of Health, who started his career in health as a malaria researcher

The year 2004 proved to be a pivotal moment in the history of Ethiopia. The country, more than ten years removed from a devastating civil war, was still struggling to deliver basic healthcare to its citizens. A malaria epidemic raged across the country. Malaria case and mortality rates, maternal mortality, child mortality, and other important health indicators were among the worst in the world. Nearly half of all deaths in the country were due to malaria and other preventable and treatable conditions.

The challenges were easy to see: the country had only 300 to 400 health centers – most of them in urban areas – leaving rural Ethiopians with no access to even the most basic healthcare. The vast majority of people had no access to proven tools to fight malaria and the malaria parasite had developed resistance to sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP), the first line drug treatment.

The country’s leaders recognized that to make progress on malaria and other key health goals, they would need to broaden and strengthen the health system. With the support of the international community, they launched the country’s first truly national health system capable of delivering primary health care and preventive care – including malaria prevention, diagnosis, and treatment – to every village and hamlet.

The backbone of this robust system, built from 2004 to 2008, is 16,000 new health posts staffed by a new corps of 40,000 prevention-focused community health workers (called “Health Extension Workers”). The health workers were trained to diagnose and treat malaria, identify mosquito breeding sites, distribute insecticide treated nets, and support household spraying campaigns. They connected thousands of remote communities across the country with the resources they needed to stop the malaria epidemics that had previously rolled through Ethiopia’s countryside every six to eight years.

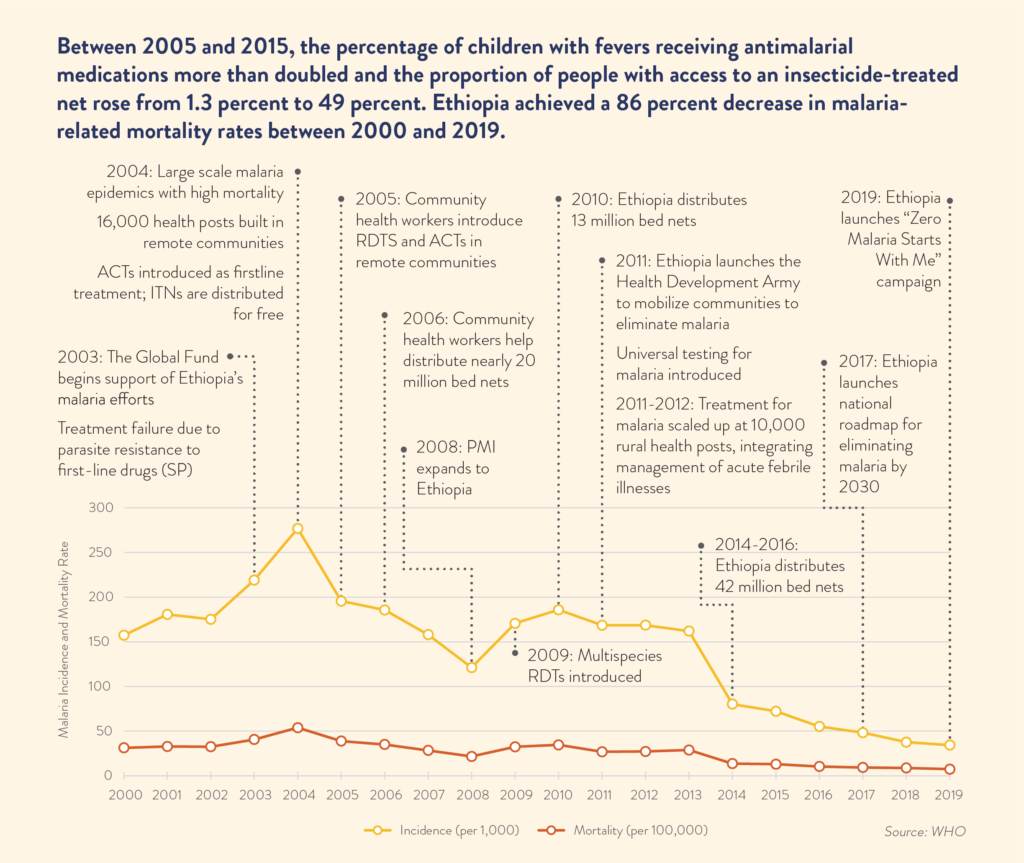

These investments would pay dividends and transform health outcomes – between 2005 and 2015, the percentage of children with fevers receiving antimalarial medications more than doubled and the proportion of people with access to an insecticide-treated net rose from 1.3 percent to 49 percent. The country achieved a 86 percent decrease in malaria-related deaths between 2000 and 2019.

Behind this historic success is robust U.S. funding and technical assistance from the President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI) and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. From training healthcare workers to procuring insecticide-treated bed nets, anti-malarial medicine, and rapid diagnostic tests, U.S. partnership was pivotal.

Eager to expand on the success of the community health worker program and achieve its goal of malaria elimination, in 2011 Ethiopia launched another prevention-focused cohort – the Health Development Army. The army’s members, three million women volunteers found in every village across the country, educate and encourage their neighbors to follow best practices to prevent malaria. This includes distributing and properly hanging insecticide-treated nets, identifying and eliminating potential mosquito breeding sites, and helping community health workers identify malaria cases.

Today, the community health workers and their “army” continue to lead Ethiopia’s fight against malaria. With continued funding and support from PMI and the Global Fund, each year Ethiopia’s Community Health Workers administer millions of rapid diagnostic tests and doses of artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACT) to diagnose and treat malaria cases. Community health workers also serve as the frontline of the country’s robust data system to detect, report, and monitor malaria incidence rates – which declined by almost 87 percent between 2004 and 2019.

Assessing this progress, Ethiopia has set the ambitious goal of eliminating malaria within its borders by 2030 and the government has committed to continuing to increase domestic financing for the program.