COVID-19 and Malaria

COVID-19 has taken millions of lives around the world, compromised health systems, and placed life-saving programs at risk – including malaria prevention, detection, and treatment.

Despite this unprecedented global challenge – which prompted lockdowns that stopped factory production of critical tools and malaria medicines, made it harder for people to access healthcare, disrupted supply chains and distribution networks, and impacted innovative research and development – the work to end malaria has continued.

Malaria programs have demonstrated resilience to pandemic disruptions and have contributed to the COVID-19 response through their broad network of community health workers, data and surveillance systems, supply chains, and program implementation platforms.

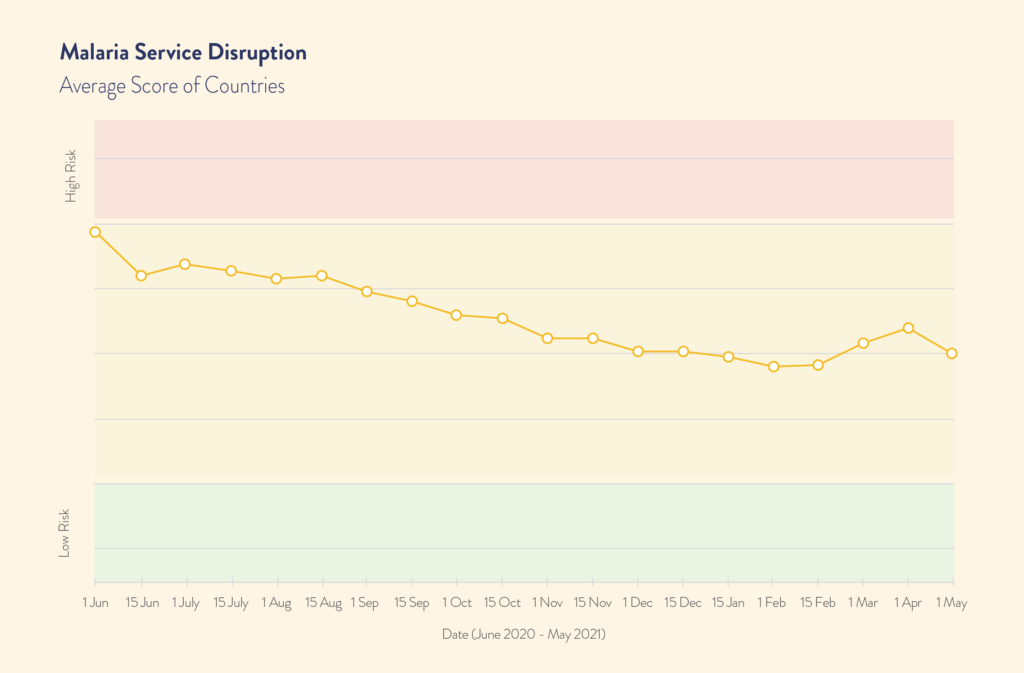

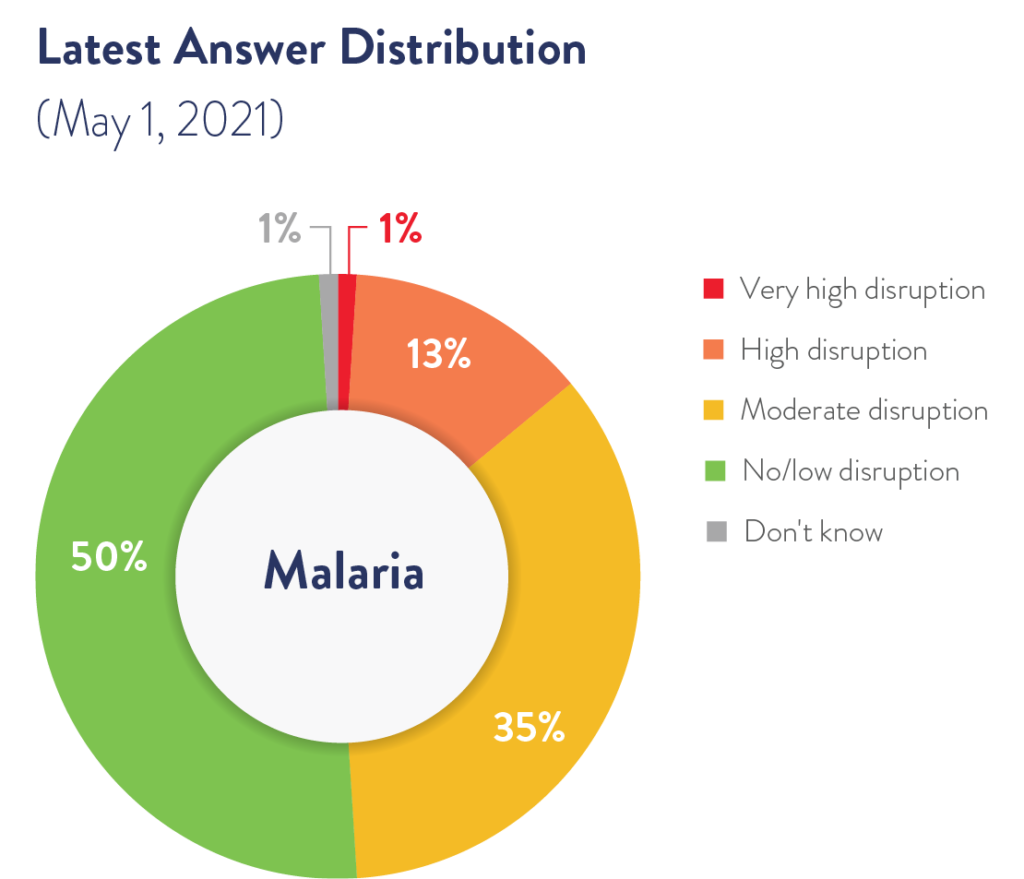

A survey conducted early in the pandemic by the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria showed that 73 percent of malaria programs reported disruption to service delivery in June 2020. Now more than a year into the pandemic, the status of malaria interventions is mixed. While 90 percent of life-saving malaria preventive intervention campaigns remain on track across Africa, Asia, and the Americas, malaria diagnosis and treatment have still not returned to pre-pandemic levels.

The successful adaptation of prevention campaigns is a testament to the historic partnership between donor and endemic countries; significant and sustained financial investments; the financial and technical support of the U.S. President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI), Global Fund, and World Health Organization (WHO); and strong political commitment by leaders around the world to continue the fight against malaria even in the face of the pandemic.

The Global Fund, PMI, the RBM Partnership to End Malaria, WHO, and UNICEF supported the development and communication of early guidance to endemic countries on how they could safely maintain malaria prevention and control services during the pandemic. These organizations and their partners worked diligently to protect the supply chain – from the factory floor to the end user – of malaria prevention, diagnosis, and treatment tools during lockdowns and border closures. When and where those supply chains and activities were compromised, U.S. funding and support, including from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, contributed to modelling analysis to quantify the potential impact of COVID-19-related service disruptions.

As we’ve seen in the case studies in this report, global efforts to end malaria have had a broad impact beyond this disease and have strengthened health systems around the world. Today, countries have more and better-trained health workers, increased lab capacity and capability, and improved disease surveillance. All of these position countries to better target, monitor, and manage new health threats starting from the community level. These strengthened health systems are more resilient and capable of functioning even during a pandemic as demonstrated across many malaria-endemic countries.

For example, the same community health workers who travel around Ethiopia distributing insecticide-treated bed nets to prevent malaria have gone the extra mile to stop the spread of COVID-19 by safely delivering nets door-to-door and avoiding large gatherings at distribution points during the pandemic. In Uganda, workers with the National Malaria Control Division have gone a step further, delivering not only bed nets to rural areas, but face masks, too. In Cambodia – part of the Greater Mekong Subregion featured in this report – village community health workers do weekly fever screenings that can help sound the alarm on both malaria and COVID-19.

Efforts like these show why so many health leaders around the world have prioritized holding the line against malaria during the pandemic. By continuing life-saving and preventive anti-malaria activities and adapting the way they deliver nets, diagnostics, and medicines to ensure the safety of frontline health workers and communities, countries have shown their resilience and leadership, saving hundreds of thousands of lives from a dual crisis.

The COVID-19 crisis demonstrates the potential impact of epidemics and pandemics on the fight against malaria. It is just one in a series of health emergencies that have challenged malaria efforts over the past two decades, including the West Africa Ebola outbreak and H5N1 influenza. Supply chain and program delays and disruptions caused by such emergencies threaten our goal of reaching a malaria-free world within a generation. But as we’ve also seen during this pandemic, the malaria infrastructure that has been built over decades is critical. It can be leveraged in times of crisis to secure health systems, continue essential services, and contribute to the detection of pandemic threats through its vast diagnostic network in remote locations.