Looking ahead to 2030 targets

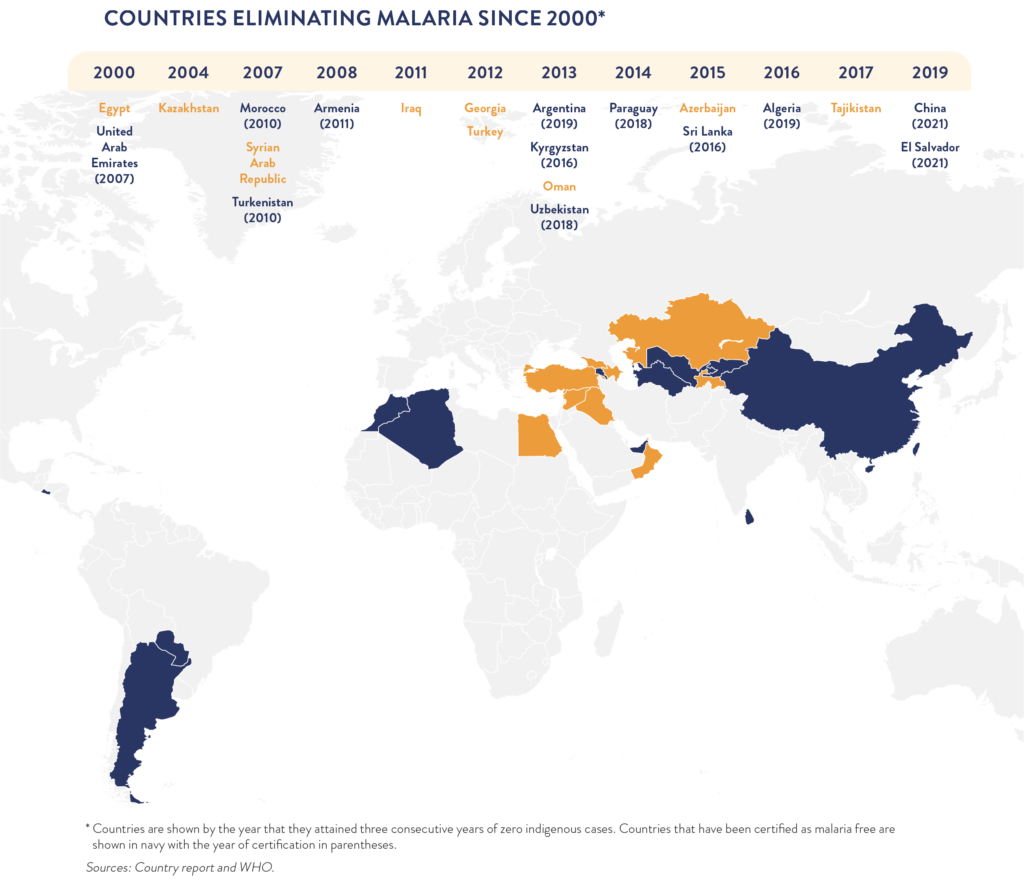

Since 2000, we have cut the incidence rate of malaria by nearly 29 percent and reduced the malaria mortality rate by 60 percent, despite a doubling of the population across sub-Saharan Africa. During these same two decades, 21 countries have reached zero malaria cases and 10 have been certified by the World Health Organization (WHO) as malaria free. Another 27 countries now report fewer than 100 indigenous cases each year – signaling elimination is within reach.

But despite this progress, we have fallen short of our 2020 milestones for mortality and incidence. Moreover, we may fall short of our targets for 2030 – to reduce malaria cases and deaths by 90 percent and eliminate malaria in 35 countries – if funding, political commitment, or technological innovations lag.

Our global fight against malaria is a relatively recent one. In 1999, total funding for fighting malaria around the world was just $33 million. Many countries, even those plagued by high rates of malaria, had no malaria control programs in place. They did not have the funding and, in many cases, the technology was not yet developed to support their efforts.

New scientific advances and the commitment of partners around the world mean that we have an opportunity today to not just further shrink malaria’s footprint in the world, but also to end it. The immense progress highlighted in this report – in El Salvador, Ethiopia, India, the Greater Mekong Subregion, Senegal, and Uganda – demonstrates that rapid improvement is possible even in some of the most high-burden places on earth. But we must ensure that health systems are empowered to reach communities with a full toolbox of powerful anti-malaria innovations.

To make further progress globally, we will need to increase our investments to cover last mile challenges in some of the most vulnerable corners of the globe. We need to ensure that bed nets are delivered in conflict-affected settings, such as Congo and Mali; that treatment is accessible in hard-to-reach indigenous communities, such as those in India and Ecuador; and that investments in developing game-changing innovations continue.

Today, scientists around the world are at work on revolutionary innovations, such as:

- Bed nets that are more effective against insecticide resistance, such as pyrethroid-PBO and dual active ingredient nets

- Longer lasting insecticide-treated nets

- Monoclonal antibody treatment to prevent malaria

- Genetically modified mosquitoes

- Malaria vaccines, now undergoing pilot trials in Ghana, Kenya, and Malawi

Today the US and global partners dedicate roughly $3 billion to ending malaria annually – less than half of the estimated amount needed to achieve this goal. Doubling that investment would strengthen health systems the world over and end a scourge that undermines economic development in many of the poorest areas of our planet and robs the youngest of their future.

U.S. and global partners currently dedicate roughly $3 billion to ending malaria annually – less than half of the estimated amount needed to end a scourge that undermines economic development in many parts of the world and robs the youngest of their future. But with right investments, scaled up interventions, and continued innovation, we can end malaria within a generation.